We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs.

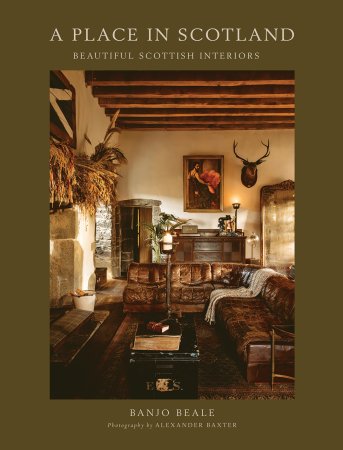

If you think Scottish design begins and ends with tartan wallpaper, think again. A new wave of architects, homeowners, and artists are quietly rewriting the rules of what Scottish style can be. Capturing this micro movement is Banjo Beale, the Australia-born, Scotland-based designer who calls the Isle of Mull home. As the star of the BBC TV series Designing the Hebrides, Beale has witnessed the change sweeping across Scotland, one where merchant houses, ancient castles, and humble stone bothies are transformed into warm, characterful spaces. The designer’s new book, A Place in Scotland, invites you inside these remarkable homes to meet the bold creatives who see potential in the forgotten and magic in the mundane. Read on for an excerpt exploring one such transformation on Beale’s home island of Mull.

This stone cottage on the rocky north coast of Mull, in the middle of a field, overlooks the sea toward Coll and the small isles of Rum, Eigg, and Muck in the Inner Hebrides. It has been a shelter for fishermen, sheep, and hill walkers, all looking for refuge against the wild west coast weather. Dun Guaidhre has stood for centuries next to the remains of an ancient Iron Age fort, or “dun.” Although it remains unchanged outside, it has had a decidedly modern upgrade, kept deliberately as modest as it always has been.

It was important for architects Peter and Rachel Harford-Cross to retain the existing qualities of the cottage. Originally built as a simple family black house, typical of those all over the Hebrides, the cottage was nearly lost to ruin at the beginning of the 20th century but was saved for its use as a sheep byre. Later the sheep were moved out and it was made habitable again to provide basic shelter from the elements. Over the years, many hands have added to and shaped this simple cottage, and their marks and interventions tell its history.

The owners and architects had a light-touch brief, focusing on simplicity and minimal intervention. Their challenge was to improve the fabric of the building without losing the basic, simple, and open qualities of the space. Budgetary reasons and a difficult site on a grassy plateau with no traditional vehicle access were two reasons for the brief, but the driving force was to create a space that was in keeping with the spirit and history of the simple dwelling, while making it robust and comfortable enough for modern needs.

It was important to preserve the existing character such as the bare stone walls, which received a plain whitewashed paint job, highlighting the deep walls that stand between the cozy space and the whipping Atlantic winds. The roof boards and beams remain unchanged, painted a light gray to reflect the typical Hebridean sky.

A cloakroom and a bathroom are the only separate spaces that were added here, behind plywood paneling. The ply was cut in irregular widths and constructed with a shadow gap to create the illusion of a hardwood boarded finish, but using this typically more affordable and lighter material. The oak and stone floor helps to anchor the space.

The living space and tiny kitchenette are concealed in a cupboard with a folding door. A generous bedroom has been cleverly zoned by a curtain, and a second camping space, or snug, just enough for two people, has been added above, accessible by a ladder.

Where materials were added they were done so sparingly and selected for longevity and quality. The furniture and fittings were also carefully chosen with this approach in mind. The space has been fitted out with secondhand furniture, from the chairs to the reclaimed ship’s light fittings to the bathroom sink, which was lying in a neighboring shed. A wood-burning range in the living space is the sole means of cooking, providing warmth and hot water. More refined than rustic, the space feels quiet and reflective.

Excerpted from A Place in Scotland: Beautiful Scottish Interiors by Banjo Beale. Published by Quadrille.